By Jennifer Schindler-Ruwisch

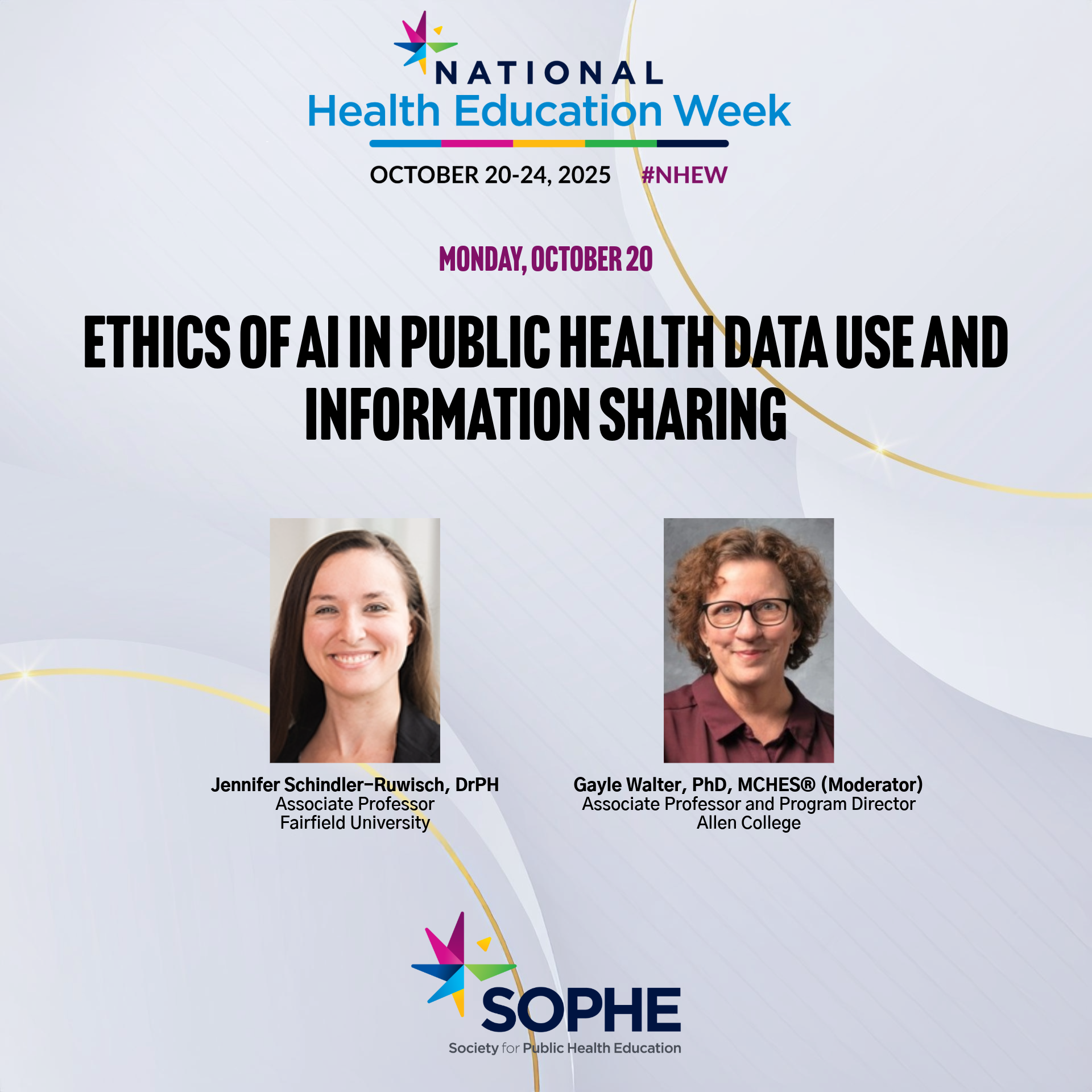

Editor’s note: This blog post is a lead into the author’s presentation on Artificial Intelligence during National Health Education Week, titled “Ethics of AI in Public Health Data Use and Information Sharing.”

Bias is everywhere, and AI is no exception. If you want a brief overview of AI bias, check out this video from the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

We know that humans have biases, and humans train AI, which can incorporate and sometimes amplify bias in AI models and algorithms. We can’t assume AI’s results are unbiased, even if the goal is for AI to be objective.

AI is using available data, which is not always current or generalizable to all populations. If we want high-quality output, we need to provide AI with evidence-based input. The data used in AI processes should be transparent, inclusive and representative.

Fortunately, there are ways to detect and even mitigate AI bias. AI is teachable, but this work needs to happen with stakeholder input throughout the AI lifecycle. Collaborative efforts to create models with insight from end-users is necessary to refine and improve model performance. Since AI can demonstrate drift in performance over time, especially as machine learning is designed to evolve independently, ongoing assessment and evaluation is necessary to retrain and revisit errors before they perpetuate bias.

AI models also pull vast amounts of “Big Data” from many public domains, webpages, social media sites and more. Not everyone realizes that every time you put data into a Generative Pre-trained Transformer (GPT) you are providing that information into a pool of data that will be used to draw future responses. Therefore, if you put in health information about yourself or someone else, that data is no longer private. Having transparent consent processes for data that will be used for future AI output are warranted. But until such monitoring and accountability measures are in place, it’s wise to be cautious about what you enter into a GPT. Some models are also trained to scrape data from social media or other “personal” pages, so even though the information is in some sense public, individuals may not realize their data could be used outside of how they originally intended.

Improving AI reliability, putting in safeguards for continuous monitoring, explainability and privacy/data security are driving policies in many places worldwide, but are not yet ubiquitous or widely enforced. Coordinated regulation and AI oversight is needed to help the innovative potential of these tools to grow, while protecting the public’s health.

It is prudent to be cautious of AI use, but it is also important to recognize that as it’s use proliferates, it can be used for good, when done responsibly. While many fear AI spreads misinformation and disinformation (and unfortunately so do humans), AI can actually also help identify and flag provider biases, misinformation, harmful language, and more, when done in partnership with public health professionals and the community.

Together we can work towards ethical AI practices and standards so that the power of AI can be used to promote and protect health, rather than cause further harm.

For more, please check out my upcoming book by Routledge/CRC Press, Maternal Health: Innovations and Transformations.